I did a thing!

You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain.

It's funny - when I started writing these essays three years ago, the idea was taking the gold hidden within the inaccessible language of psychological literature, and turning it into something (hopefully) fun & engaging to read. Now, last week, I finally got to see my first study published in a scientific journal: "Accept the Stress? Examining the Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies to Explain the Relationship between Mindfulness and Burnout". And as you can probably gather by how long the title is, I too was corrupted by academia. To get published, you have to play by the rules, and write by them too.

Luckily, out here I can write by my own rules. So in a funky roundabout way, today I get to cite a study I know rather well because I did it myself, and tell you about what I learned along the way. About how stress works, about the helpful & unhelpful ways we handle emotions, and how our choices affect our outcomes. And centrally - about the role that mindfulness plays in all this.

That's the thing: When I started out, I had a question I wanted to study: Is there an effect of mindfulness on Burnout? I went off into the wide world of PubMed and read all the studies I could find, only to be quickly faced with the reality that my "question" wasn't really a question. In a whole range of meta-analyses (studies that review hundreds of other studies on the same topic and present the results), there was a clear consensus: There is a protective effect of mindfulness on Burnout.

What was less clear, and more interesting to me: Why though? How in the world would focusing on your breath at the tip of your nose prevent the inevitable stressors of life from sending you over the edge right into Burnout?

The answer to that question, surely, is multi-faceted and complex - way more than anyone can capture in a single study. Yet, you gotta start somewhere. So, based on the literature, I landed on Emotion Regulation as a potential mechanism. The idea: Mindfulness may change the way that we relate to and manage our emotions, and thereby dampen the effects that stressors can have on our wellbeing.

At this point in the scientific process, we land at what is called "operationalisation". We have a hypothesis (= an idea we want to test), and it's full of wonderful words:

H1 = Mindfulness has a protective effect on Burnout by changing Emotion Regulation.

However, it's pretty hard to test words. We need to define exactly what we mean by these words, and how we're going to measure them. This is where we get to the cornerstone models of the study - the ways in which we assume the mind to work. In the paper (and indeed in past essays), I describe these in more detail - but I still wanted to bring them in here because I truly find them helpful for making sense of every day life.

Chapter 1: Burnout

First, to understand what could protect from Burnout, we need to understand how it arises in the first place. Stress is natural, inevitable in basically any endeavour life has to offer, yet not everyone burns out. Why?

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model gives us the framework here. I have a whole essay on managing stress that explores this more deeply, but for today's purposes, let's stick with the fundamentals. The core assumption, and an important distinction to make, is that Burnout is more than physical fatigue - it's also characterised by emotional exhaustion, showing up in a sense of disengagement and cynicism about work. So, how do we get there?

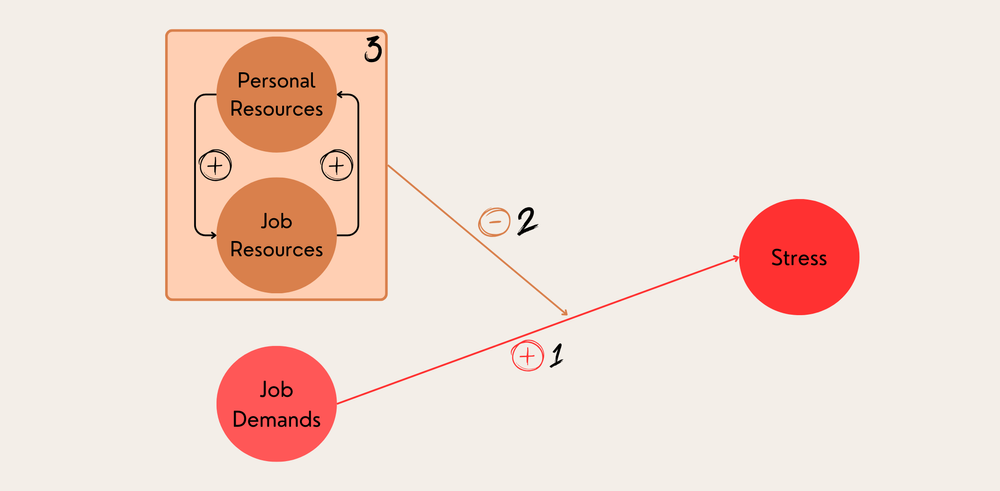

The model has three main ideas:

- Job Demands are any work aspect that puts an ongoing strain on you - think deadlines, navigating change, annoying boss, having to smile at customers when you're dying inside, ...

- Resources are anything that helps you achieve work-related goals

- Job Resources are work aspects that help you out - think great coworkers, autonomy, feedback, ...

- Personal Resources are individual characteristics affecting your stress management - think social support, the relationship with your dog, or maybe mindfulness?

- Stress is the felt bodily and emotional sense of strain. You know what stress feels like.

These ideas are related like this:

- Job Demands directly lead to Stress. Duh. If that stress is more than you can manage for a while (i.e. is chronic), we get to Burnout: Neverending fatigue, a cynic attitude and aloofness.

- Resources negatively moderate this relationship. In English: They buffer the effects of Job Demands - The same demands lead to less unmanaged stress.

In this way, Burnout can be understood as a protective mechanism: There are inevitable stressors that have an emotional impact, and when that impact becomes too much to handle, we seek emotional distance from it - we disengage and become cynical about our work. It's no coincidence that Burnout emerged as a concept in research around nurses - people that (on top of the physical fatigue of working looong hours) literally care as a job. That is, until they can't care anymore - this is emotional exhaustion.

So, what do we do about this? The model gives us three factors we could potentially change to reduce the level of unmanaged stress: Job Demands, Job Resources and Personal Resources. For the stressed and unwell, reducing Job Demands is rarely in their control. The idea of tailoring your role to provide more Job Resources (so-called Job Crafting) requires a lot of engagement with your work - so that's not an option either. What's left: Personal Resources.

Basically, we find ourselves in a situation where stressors are inevitable, and their emotional effects are too. Naturally, how we manage those emotions when they arise is gonna play a massive role in how much we're impacted by the underlying stressors. And in psychological terms, "how we manage those emotions" is called Emotion Regulation - the next part of our Hypothesis.

H1 = Mindfulness has a protective effect on Burnout by changing Emotion Regulation.

Chapter 2: Emotion Regulation

Back in the olden days of psychology (late 1800s), the predominant theory of emotion held that what we feel as emotions are simply what some automatic physiological process feels like. "Do we run from a bear because we are afraid, or are we afraid because we run?", William James famously said, and his answer was quite simple:

My thesis, on the contrary, is that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur is the emotion.

Now if this was true, we could stop here. Stress causes emotional reactions, and they cause Burnout, and there's nothing we can do about it. Buuuuut he was wrong.

Meet Gross' Process Model of Emotion Regulation. One of my first-ever essays was all about using this model as a decision framework when things get funky, but for our purposes these are the essentials:

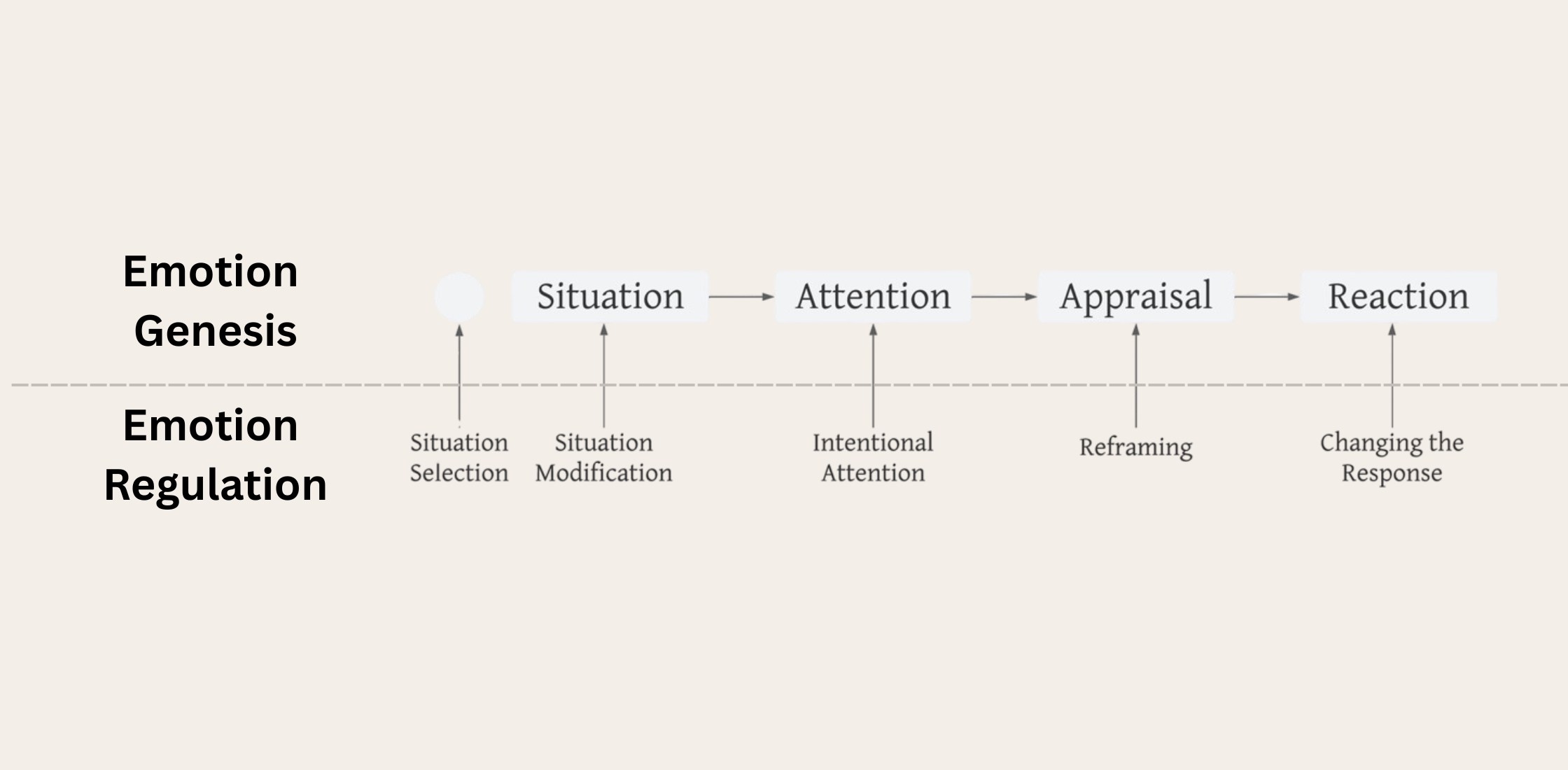

- Emotion Genesis: Emotions arise following a four-step process:

- Situation: You find yourself in a situation that's emotionally relevant to you.

- Attention: You become consciously aware of the situation.

- Appraisal: You evaluate the situation - good, bad, dangerous, catastrophic?

- Reaction: Based on your evaluation of the attended situation, an emotion arises.

- Emotion Regulation: At each point of this process, we can potentially intervene to change the outcome.

How exactly we intervene in this process is different for everyone - based on how we grew up, what worked for us in the past, what we were taught is right and wrong - but as with everything ever, there are patterns, and we can look at them from two angles.

First, we can sort these approaches to regulation - the literature calls them strategies - into the process model based on where they aim to make a change. For example, avoidance is a Situation Selection strategy because it targets the emotionally-charged situation before it even starts. Suppression is a Response-Focused strategy because (duh) it targets the emotional response after it arises.

After identifying the different strategies that people use, we can then look at their habitual emotion regulation - which strategies they tend to use more often. This is important because - second - different strategies differ on their adaptivity - how healthy they are over time.

Of course, everything is context-dependent to a degree: Avoidance might be an adaptive (= great and healthy) strategy when you skilfully decide not to go back into a toxic relationship. It's adaptive here because that the short- and long-term effects of your choice are positive. But more often than not, avoidance is used for short-term relief at long-term cost.

Take Social Anxiety Disorder: Someone feels scared of social interactions, so they avoid going out. Short-term, this is a great success: The fear is gone, and emotions are regulated. Long-term, however, the lack of interaction makes going out even more scary, leaving them even more isolated, and reinforcing the cycle until we get to a clinical disorder. Your strategy is just making things worse - this is what we call maladaptive.

To make this distinction for any strategy, we have to look at what happens over time - If there's a strong link between habitually suppressing your emotions and depression scores, chances are pretty good this is a maladaptive strategy. So, using our good friend (the meta-analysis) and looking at the links between habitual use of any strategy and mental health outcomes, we find adaptive and maladaptive strategies.

Cool. That was a looooot of input, and I hope it all made sense so far. We now have an idea of how Burnout arises, see the importance of successfully self-regulating when stressors arise, and know that people differ in their habitual use of adaptive & maladaptive emotion regulation strategies - which shows up in real conditions. All we need is a practical way to help people self-regulate, and we might have ourselves a winner. If only we had a hypothesis for that...

H1 = Mindfulness has a protective effect on Burnout by changing Emotion Regulation.

Chapter 3: Mindfulness

The last model only takes four sentences, and we'll call it trait and state mindfulness. State mindfulness describes a way of being in any moment: attentive, non-judgemental, present - what people experience when they meditate, for example. State mindfulness is situation-specific: How mindful are you right now, in this situation? Trait mindfulness is simply someone's tendency to in that mindful state at any point in time - it is cross-situational: How mindful are you on any given day? When people meditate regularly, they experience state mindfulness regularly, which grows in their trait mindfulness over time.

Finally made it - this is what I tested. People's levels of trait mindfulness, levels of burnout & their emotion regulation habits. All in a fancy statistical method called parallel mediation to determine if Emotion Regulation explained the effect of Mindfulness on Burnout. The answer was:

Kinda. As expected, more Mindfulness was linked to less Burnout. As expected, more Mindfulness was linked to more adaptive Emotion Regulation, and less maladaptive Emotion Regulation. But it wasn't that broader shift in habits that made up the mechanism. There were only two strategies that significantly mediated (= explained) the effect of Mindfulness on Burnout: More Acceptance and less Rumination. Just because both of these strategies are often misinterpreted, let me sneak in two more definitions before closing with what I take away from the data, and this whole process.

Acceptance is often confused with resignation - but I feel like that's almost a wording error. Indeed, I prefer the term "Acknowledging", because at its core it's simply the act of recognising something that already is there. As a response-focused strategy (in the process model), it comes after the appraisal of your control over the situation. One of the questions that's used for measuring acceptance is "When I could not change something, I accepted the situation as it was", which is above all a wise conservation of energy. Humans have a marvellous tendency to reluctantly tense against the inevitable, and waste a whole lotta life force doing so. Within the confines of context-dependency ("Acceptance" of something you can actually change isn't Acceptance in the scientific sense - that's resignation), releasing the mental knot that had you tied up in something entirely out of your control can only free up more mental energy for the things actually in your control. It's no surprise that this would buffer the impact of all the inevitable vicissitudes of being in the world. It's also no surprise that mindfulness would be hugely conducive to this strategy - Sitting with what is, as it is, without judgement, is the entire idea of the meditative practice.

On the other hand, there's Rumination. It's often confused with problem-solving, when in reality it's the exact opposite. Rumination is the tendency to brood on, to think repetitively about the things that bother you. Going in circles and never getting anywhere, this tendency loves to masquerade as "paying attention to something worth paying attention to" - but that's exactly all it is. As an attention-focused strategy (in the process model), it never arrives at the point of situation modification (which is where problem-solving lives). Instead, it just goes around and around in circles, keeping attention on the situation that causes you stress, but nothing more. It's no wonder that this tendency is considered a maintenance factor for depression (aka "keeps it going") - and it's no wonder that it only amplifies the effects of a workplace stressor, instead of buffering against it. After all, if your boss is rude to you on a Friday, and you spend the entirety of Saturday and Sunday brooding on his rudeness, how recharged will you return on Monday? Lastly, it's no wonder that mindfulness would reduce this tendency. In a meditative practice, you learn to observe the mind and its patterns, to interrupt where necessary - and on that dizzying roundabout of rumination you may indeed benefit from taking an exit - maybe the problem-solving one (if that possible), or the acceptance one (if it isn't).

It was pretty fascinating - what the data showed is captured in the Buddhist metaphor of the two arrows. The first arrow describes the inevitable pain and strain of living a human life - stressful deadlines on the job, or feeling hurt when your boss is rude to you. It's unavoidable & it's gonna remain that way for the foreseeable future. The second arrow is all that add-on suffering that a human mind likes to gift on top - sleepless rumination spirals, blaming yourself when your boss was rude, replaying painful moments in your head over and over and over again. The second arrow is optional, and put very simply, mindfulness is about shooting yourself with the second arrow a little less.

Or, in the terms of the JD-R Model: Job Demands are unavoidable, but with enough Personal Resources, Burnout isn't. Importantly, this is by no means an attempt to blame ridiculously overworked healthcare workers for their Burnout - working on Job Demands & Job Resources should of course be a priority for those in the positions to change them. Conversely, research like this is simply an attempt to bring some relief to those that aren't in a position to change them, and learn something about the way the human mind works along the way.

If you've read this far, respect. I've tried my very best to keep this accessible, but I'm aware it's a lot of content - it was a whole dissertation, after all. Hope it's been a fun read :)

Lastly, on a personal note: I'm quite fond of this research project, for it's the entire reason I meditate. When I started four years ago, I was convinced meditation was some unscientific woowoo stuff. Throughout the writing process, I guess being confronted with all this evidence to the contrary every day made it feel silly not to give it a shot. "I can't be writing about this proven thing and then not do it", I thought. So I gave it a shot indeed, and four years later I've sat multiple retreats, with something like 3000h of practice, and I instead of unscientific woowoo, I've found it to be quite similar to the scientific method - just inwards. You're just observing how your own mind works, the patterns that emerge, the good and the bad and the ugly, as they arise. There's a journal entry I wrote a while ago that captures this:

4 October 2023 at 1:37 pm

As the scientist conducts his experiments to investigate the nature of a certain phenomenon, so do we investigate the nature of mind and the laws of everything around us. Now, does a good researcher in search of the truth have a preference regarding his observations? Does he aim to get a certain result? Or is he grateful when an unexpected result arises for its presence has broadened his understanding?

In the same way, walking through life with the aim of understanding the nature of ourselves and our surroundings, whatever arises carries with it the chance for understanding, right? Be it pleasant or unpleasant, the investigative lens is non-preferential. It is precisely the variety, vividness and breadth of what arises that allows for a deeper understanding.

So, my guess as to why mindfulness is linked to more adaptive and less maladaptive emotion regulation is that stronger sense of inward understanding - knowing when you're hurting yourself, when you're lying to yourself, or when you need help. Buuuuuut that's just a guess - I have no data to back it up (yet).

Comments ()