Where do I even start?

This week, a friend asked me if I ever feel stressed.

"Of course I do, I'm only human too", I said, slightly confused. "So how do you handle it? Do I have an essay for me?", she wondered further. And I went through the archives only to find I don't.

My scientific baby is a research paper on stress and meditation (which got accepted for publication this week btw, big yay). But 50 pieces in, I've written on the most ridiculously niche things - bathing cats and pointlessness - without ever considering the fundamentals. Probably because it's a big, scary question:

How do you handle stress?

Of course, this can be taken two ways: It could mean a general "What's the best way to handle stress?", which is something I won't even pretend to have an answer to. All I can offer is the alternative: "What are some of the ways this one dude scrambles to make it work somehow?" So this is what you're getting:

- What I've learned about stress in my scientific work, and

- How I fill it with life in an attempt to stay reasonably sane when things go south.

But first, a disclaimer. You'll find as we progress that stress is a deeply individual and situational matter. There's no one right way for all people. There's not even one right way for one person. What I do might not work for you, hell, it might not even work for me in another situation. There's no magic formula.

Instead, I like the idea of a tool box: In learning to manage stress, you build a collection of tools and then learn to apply them in the right circumstance. My screwdriver might fix my wobbly chair wonderfully, but it won't fix your flat tyre, neither will it help with the water in my basement next week.

This is why I won't go into too much depth on any screwdrivers. Instead, you get a framework for thinking about stress, and some potential tools to play around with. Enjoy :)

Demands and Resources

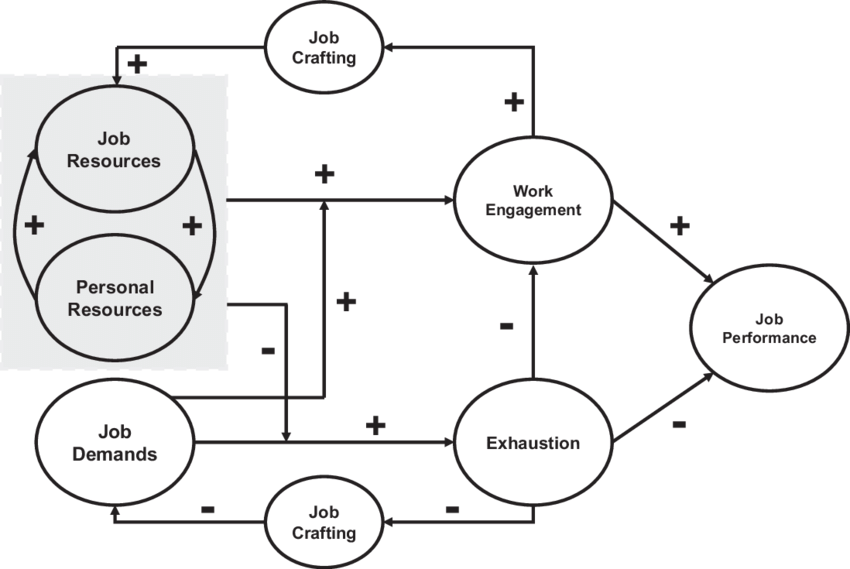

All my work around stress builds on the beautiful mess above: The Job Demands-Resources Model. For a whole breakdown, you'll have to wait until the paper is published (hopefully super soon), but for our present purposes we can simplify it a little:

What we can take away from the model is this:

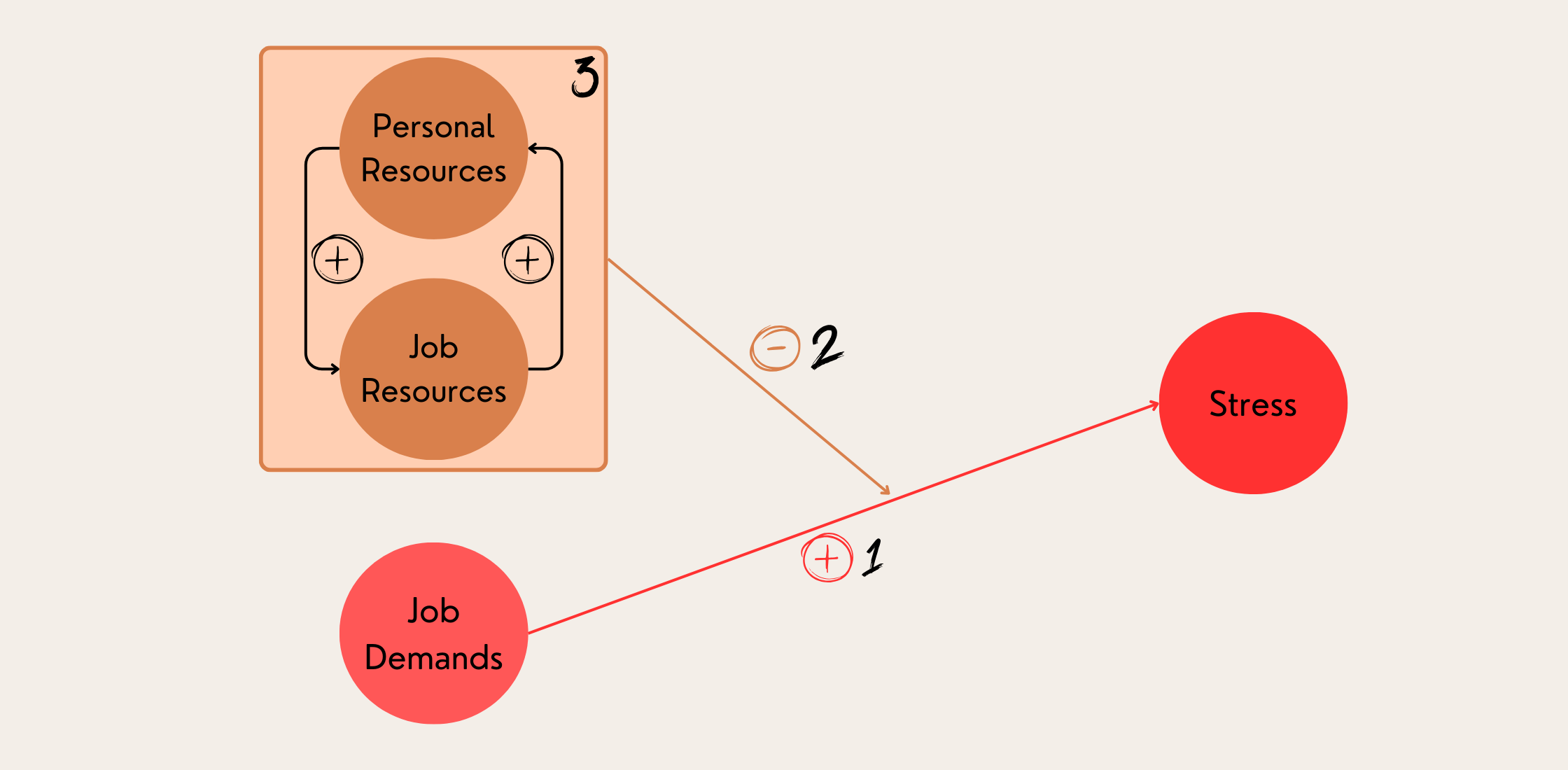

- Job Demands (any work aspect that puts an ongoing strain on you - think deadlines, novelty, change, ...) directly lead to stress. Duh.

- Resources negatively moderate this relationship. Or in English: They mitigate the effects of job demands, acting like a buffer.

- Job Resources (any work aspect that helps you achieve work-related goals - think social support, autonomy, feedback) are only half of the resource story:

Equally important are Personal Resources (any individual characteristic affecting the perception or managing of stress).

With these points in mind, we can understand stress as a sort of signal. Just like "feeling cold" signifies to the conscious mind that there is a change in temperature, "feeling stressed" signifies that there's a bunch of demands on you right now.

So far, so lovely. A signal isn't good or bad, right? I don't hate my thermometer if it shows two degrees, nor do I praise it at thirty-two. But it feels like what we usually mean by "stress" isn't just a demand thermometer, right?

To understand why there's even anything to "handle" here, we gotta dive into the idea of stress a little deeper.

Eustress and Distress

So stress, by itself, should be a value-free term. It points mainly to nervous system activation: The body is getting ready to get on with those demands signified by the thermometer. But in our colloquial language, it isn't value-free at all. Why?

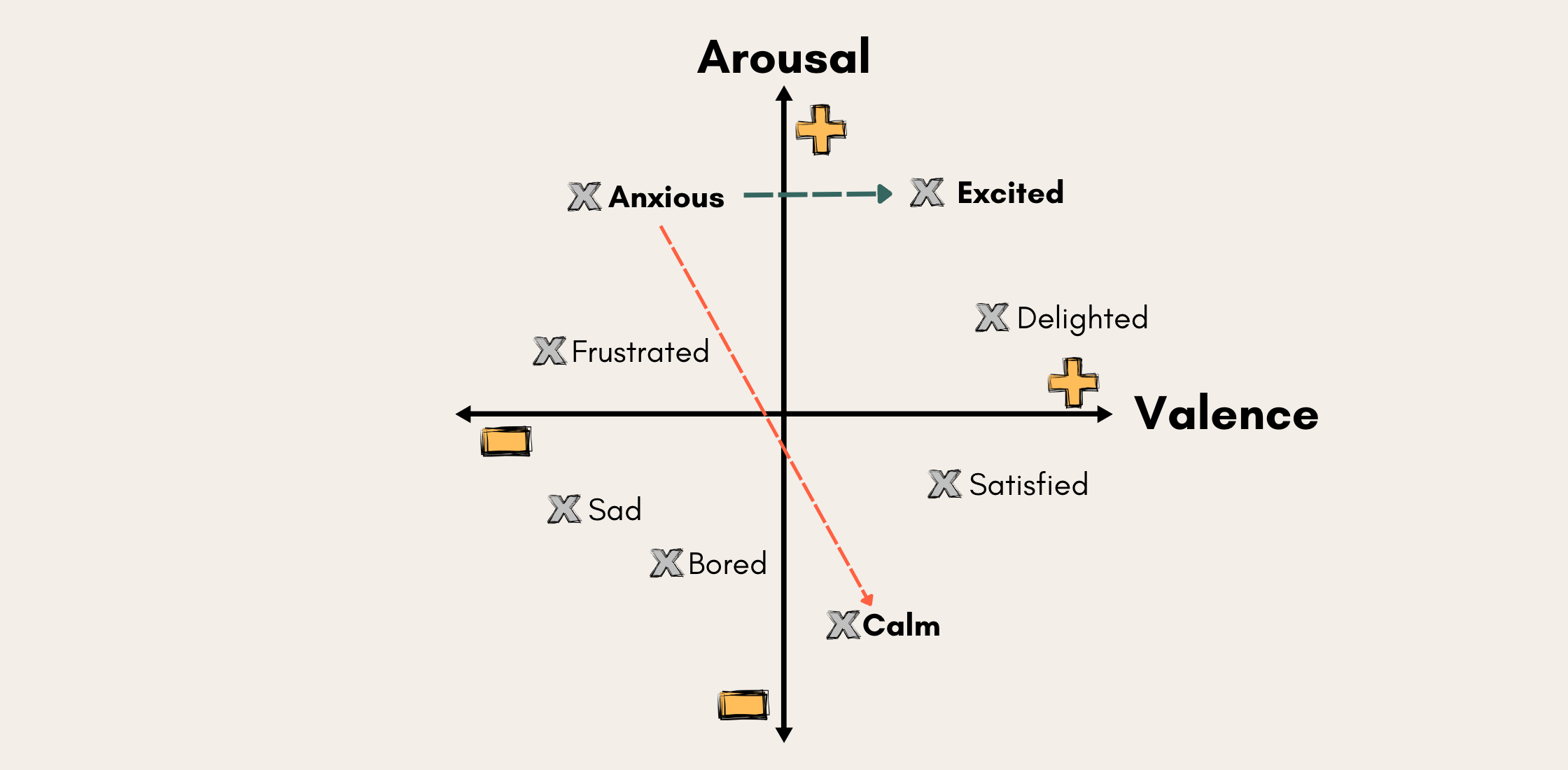

To understand, let me bring back a map from last year's "Turn Anxiety into Excitement" piece:

➕ High Arousal means you’re ready for action.

➖ Low Arousal means you’re relaxed

➕ Positive Valence means it feels good.

➖ Negative Valence means it feels bad.

Quite analogous to Anxiety and Excitement, we can map the two forms of stress: Eustress and Distress:

Eustress is defined by high arousal and positive valence. It's that state of "Let's get into it!!!", feeling fully energised in the face of a mountain of work, eager to climb that baby step by step. A lovely state indeed, obviously connected to excitement. But this is not what we usually mean by stress, it it?

No - that would be distress. High arousal and negative valence. Feeling overwhelmed by the mountain with no idea where to put the foot first. Not even sure if you can get up there at all, probably contemplating turning around and admitting defeat, but still feeling like you still have to get up there somehow. Play this game long enough, et voilà: Burnout. Not so lovely after all.

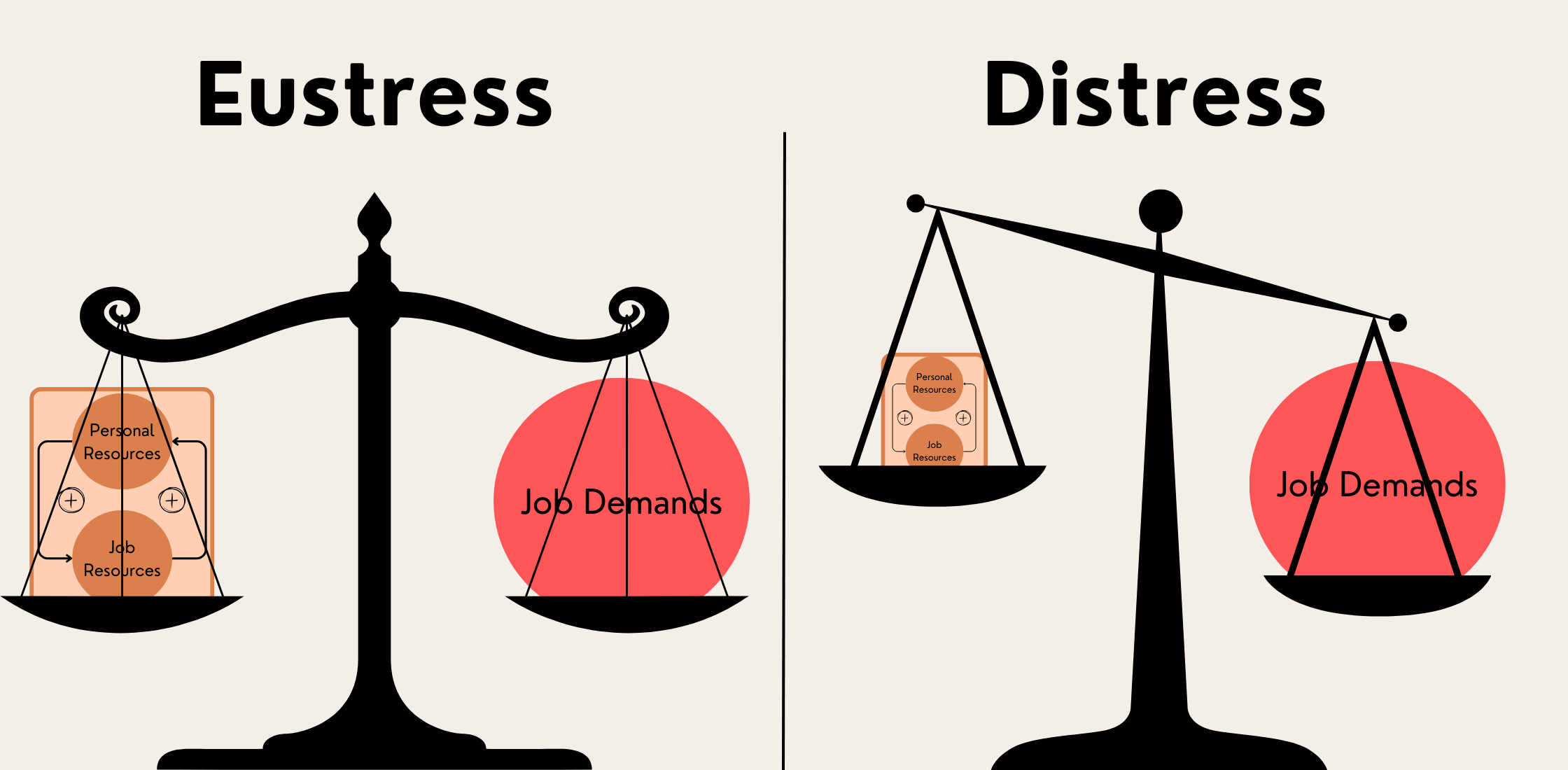

So, what's the difference between the two? That's where we come back to the JD-R. Remember how resources moderate the effect of stress? They do, but not by getting rid of the activation. Even with all the resources in the world, climbing a mountain requires heaps of effort, which in turn requires your sympathetic nervous system online & ready to rumble.

Instead, the difference is one of valence. If, backed by your resources, you have all reason to believe you'll rock that mountain, it's an exciting adventure. A Patagonia backpack full of tools, you're far from relaxed but even further from giving up.

But if you feel completely overwhelmed at the mere sight of the mountain, with some chopsticks and a half-empty water bottle in hand, the feeling is understandably different. It's the mismatch of demands and resources that leads to distress, not the mere presence of demands. The problem are more the chopsticks than the mountain.

And this is good news. Why? Because it gives you leverage. In most cases, you don't have control of your demands. Doing cool stuff usually comes with a degree of stress. Deadlines are demanding, and as long as your thermometer isn't broken, that means feeling stress. This is perfectly okay. Indeed, it's helpful because it puts your body in the necessary state to deal with those demands. It's simply a cue to open up that toolbox and find the right one for the job. And as it turns out, this little shift has some profound implications.

Perspective

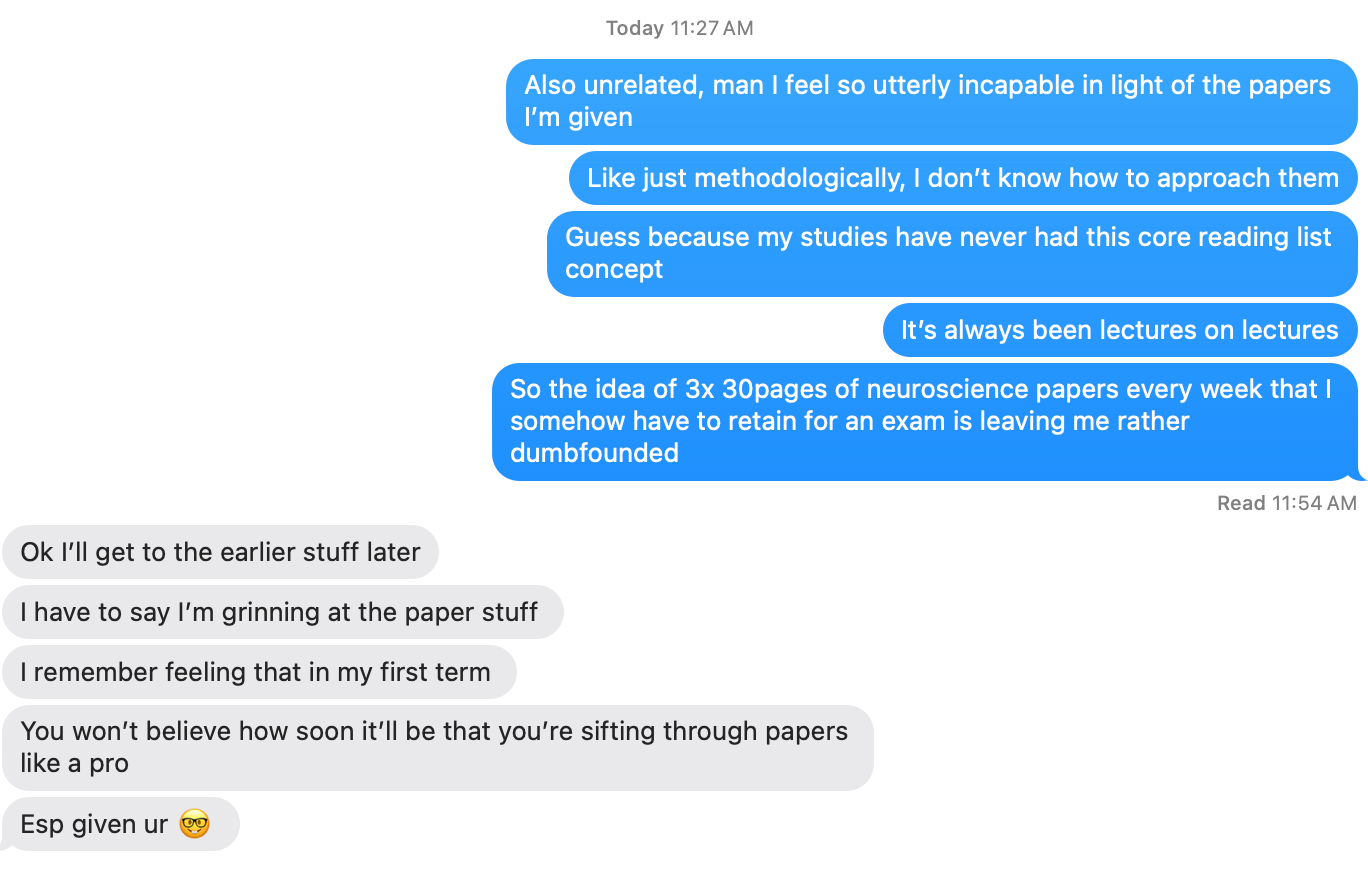

A prime example came a few weeks ago, fresh into my new degree. I felt entirely unprepared for what I was doing. In a classic case of "Where do I even start??", I spent more time worrying about reading papers than I did reading papers. And texting my friends about it. In my mind, this was a real problem. Good thing I was set right real quick by good ol' Roman:

I come to him with a problem that's been on my mind all week, and he's grinning and calling me a nerd - even worse: by using an Emoji??? The nerve, eh? Well, I'd love to be mad if it hadn't been supremely helpful. What he's doing is simply questioning if it's even a problem.

Of course, it wasn't. Nothing's wrong here. Learning Neuroscience is hard. Climbing a mountain is hard. My thermometer isn't broken, so I get the signal: This is hard.

Now, I can either worry about the fact that this feels hard, or I can work on my capacity to read papers by reading papers. Of course, one only contributes to my stress because I'm a) constantly thinking about it and b) not doing anything about it. And the other simply responds to the signal. One is like trying to tinker with the thermometer when you're cold, and the other is simply putting on a sweater.

This is only one example, but the point is that of subjectivity. The effect that a specific stressor has on you isn't predetermined by the stressor. The very same stressor (e.g. heaps of papers to read) can either be the source of distress (see my messages) or eustress (see the study sesh after I got the reply).

There is an interpretive layer between any stressor and any stress reaction, and to simply see stress as the perfectly natural function of your thermometer can make a huge difference. Not by virtue of some kinda magic. Simply by freeing up your mind to respond to the signal. Not fixated on the fire alarm, but chucking some goddamn water on that particularly chargrilled Broccoli.

Of course, this is only a screwdriver. Works well in some cases, but won't "solve stress" for good. After all, even prolonged periods of Eustress can take a toll on you. Climbing a mountain is hard, and all that. What we need, then, are some solid fundamentals.

Fundamentals

The realm of personal resources is almost endless. Individuals can find their personal superpowers in the most niche things, and that's wonderful. But unlike me & my essays, let's get the fundamentals right before everyone can find their own niche.

Especially in times of high stress, we love to compromise on the bare minimum. I'm talking the things everybody knows:

Hidden in plain sight because they're so simple, these points are incredibly powerful. I know it's almost glorified in some bubbles to pull all-nighters and eat take-away every day, and every once in a while this might work. But you're not climbing a mountain that way. After all, we're not talking some nice luxuries here. In the words of Dr Julie Smith:

Things like your ability to move, sleep, eat well, and have social connection - they're weapons of war, right? You know, if you've got a prisoner of war, the way you break them is by messing around with those things. So let's not do it voluntarily to ourselves every day.

Now I absolutely understand the appeal of skipping a workout (or ten) when the exams come around - and don't get me wrong, I've done it many a time. Ironically, when the deadline for the paper (on the benefit of meditation in stressful times) approached and times got stressful, my meditation practice went downhill real fast. Great stuff - but a common experience, I feel, given this old Zen saying:

You should sit in meditation for twenty minutes everyday - unless you're too busy; then you should sit for an hour.

Naturally, this isn't limited to meditation. It goes for all of the above: When it's crunch time is when we need our sleep the most, when we need the support of others, when we have to balance the cognitive load with movement. And of course, if I put bad fuel in a race car, it's not gonna go anywhere. Nobody does their best work when they're miserable.

Counterintuitively, sometimes the "most productive" thing you can do is go have a chat with your friends, or call it an early night. You better believe the mountain climbers are getting their 💤💤💤.

Kindness

In summary - be kind to yourself when you're stressed. It's okay. Take a break. Or get into it. Talk to a friend. Go for a walk. Or pull that all-nighter if you truly feel like it. There's no right way, and it's a constant matter of figuring it out as you go. The key is, slowly but surely, building your own toolkit.

These days, stress is a regular part of my day, like feeling hungry when I haven't eaten or feeling cold when I forgot a sweater. But when I'm hungry, I eat instead of worrying what's wrong with my stomach. And when I feel cold, I go find a spot that's less windy instead of contemplating why past me didn't put on enough weight for the winter.

On a good day, I do the same with feeling stressed. And on all the others, I'm out here trying to fix flat tyres with screwdrivers because lord knows I don't have this figured out either.

Comments ()