Your Thoughts are Not Facts

Flip, Flop. Flip, Flop. Flip, Flop. If you’ve ever taken a ride on the pendulum of indecision, you know how dizzying it gets. So dizzying that it becomes hard to get off, just leaving you flip-flopping along. Sure, big decisions in life require some consideration. But what’s the right amount of consideration? When does it become a pointless exercise in overthinking?

Well, there’s this old Zen saying that goes “A fool that persists in his folly will become wise.” In other words: If you try something pointless hard enough for long enough, you’ll eventually recognise its pointlessness.

Introducing the fool of today’s story: Me. Admittedly a chronic fool for the pendulum of indecision, perpetually convinced that I’m just giving it the required consideration, I spent the entirety of my recent trip to Asia flip-flopping. What was supposed to be a peaceful time disconnected from work was quickly hijacked by the question.

Off the back of a slight existential crisis and not entirely happy with my job situation, I spent the trip eyeing that very attractive red button. The button that says “Blow shit up.” and promises a restart in a new place with a new trajectory. I’d done it before, I thought, so I can do it again. The button was there, ready to be pressed. So the question was: Should I press it?

Enter the flip-flopping. Some mornings I’d wake up entirely convinced that I’m gonna do it. It felt clear as day, the entirely obvious choice. Cool, so that’s what we’re doing when I come back. But two days later, I’d wake up incredibly excited to make this thing work. The benefit of a start-up is that nothing is rigidly defined and every role is deeply malleable. “To quit now would be like throwing away a clay ball because you don’t like the shape.”, I thought.

Okay, so no blowing up yet. Got it. Unless… - yeah, you guess it: Another day, another flip. Another day, another flop. Much to the dismay of Roman, who had the joy of travelling with this fool, I continued my folly for weeks. Every day another certainty, and every day I latched onto it. I swung with the pendulum, fully onboard with whatever decision happened to be flavour of the day.

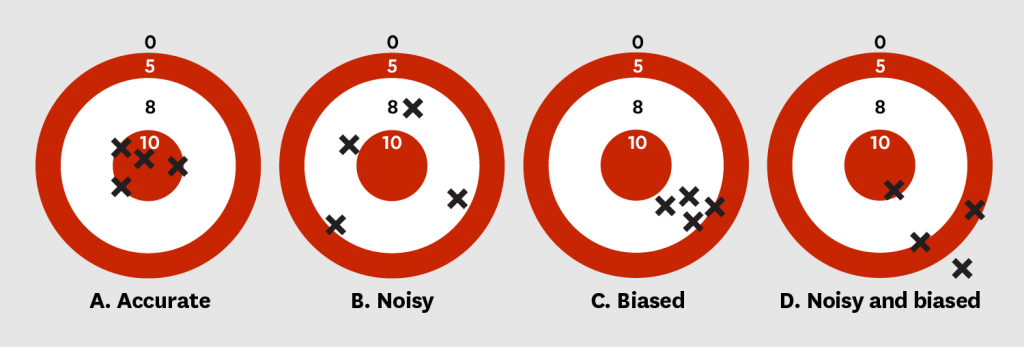

It wasn’t until we started making a joke out of it that it clicked for me. This was decision noise. A term coined by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman in his seminal book (of the same name, “Noise”), it describes the variability in our judgements that isn’t due to differences in relevant data.

For example, several studies show that judges sentence more harshly following a loss by their local football team and more leniently following a win - their mood influences their judgement. Similarly, doctors are statistically more likely to prescribe opioids later in the day - the more stressed they are, the more attractive is the quick-fix pill.

The TLDR is: There’s more going on in our judgements than meets the (mind’s) eye. The judges aren’t aware of the influence the football match had, neither do doctors look at their watch and think “Oh, 3pm, better go throw some Oxycontin at people!”. In scientific speak, the real world is full of confounding variables (→ hidden influences) and we have no idea what happened to be salient at the time of decision-making. Here’s what I wrote in my journal that day:

What have you taken from the flip-flopping? Whatever your mind presents you as fact might very well be a figment of the day’s events or just the way you slept. If your mind objects are this volatile, what makes you think they should be taken to be evidence?

However, this wasn’t about figuring out the exact confounding variables. I couldn’t care less about the exact effect that hours slept would have on my decision. Putting a name onto it did something much more important: I got off the pendulum and got to watch it swing back and forth from solid ground. Again straight from the journal:

I learned to ride out the flips and the flops, not giving either too much weight. Understanding that they both just represented the two extremes of a false dichotomy, the answer was hilariously simple: Just experiment. In the absence of certainty - which flip-flopping is - just try. Instead of futilely attempting to work out the right thing in the realm of ideas, the best way of answering the central question (”Can I form this clay ball so that it leads to wellbeing?”) is to fuck around & find out.

But this goes much deeper than decision-making. It's a fundamental shift in relating to our own minds. Our minds make up stories - and that’s not a problem, that’s what minds do. The problem arises when we start taking them as facts. Instead of seeing them as mere phenomena with a myriad of causes and conditions, we get tangled up with them. Identified with them. It’s the difference between “I am angry” and “I am experiencing anger”. The difference between “I am worthless” and “I am noticing a thought of worthlessness”.

This skill - stepping away from a thought or emotion and seeing it for what it is - is called Defusion and marks the first step in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). It’s the act of getting off the ride and realising how dizzy you were the whole time. Only then can you see clearly and start questioning with curiosity: Am I really worthless? Is this a fact? Does it hold up in court? More often than not, the answer is this:

They are fallible, susceptible to the time of day and the football team. That’s not a problem, that’s the way the mind happens to work. But as long as we latch onto the theme park rides of the mind, we get dizzy and confused. It’s only when we learn to watch the theatre from a comfortable distance that we recognise our real role in it. You are not your thoughts, and your thoughts are not facts.

Comments ()