The Opposite of Dissociation

When you dive under a wave and come out the other side, there's this moment where the saltwater runs down your eyes and your vision goes all blurry. Blink a few times and the sharpness returns. And with it comes a very distinct feeling. Heart rate slightly slower from the cold water on my face (a reflex called bradycardia), I see the horizon crystallise from a vague hint to a clear line. Tip of the board becoming an arrow pointing at the sun, it becomes obvious:

"I am really here."

Unstad Beach, Lofoten, Norway

Not that I wasn't there before: Surfing isn't the sport to be distracted in. "Eyes on the horizon", my friend Josh kept telling me when I got lost in our chat and missed the house-sized wall of water headed our way. But attention and awareness are two separate things (with separate neural mechanisms).

I was paying attention, alright. Not getting smashed by waves, maybe even catching some, looking over that very same tip of the board at the same horizon quite attentively. And it all still looks exactly the same. But in these moments, it feels like I'd been dissociating for the last twenty minutes.

Not dissociating in the psychopathological sense. It's more like the sense of distance between me and the experience that seems to collapse. As if I'm really seeing the things I'm seeing, the recognition in mind that this is all there is, and I'm indeed in right here in the middle of it. It's the opposite of dissociation - maybe association?

Not quite. Sensory reorientation (this realignment with sensory input after disorienting experience) is merely an accidental pathway to a therapeutic technique called grounding. No need for crashing waves either: just include the bottom of your feet in your awareness, right now. Take a look around the room, and notice how everything might seem a little more real already. Include a breeze on your skin, or the sensation of your fingers touching the phone you're reading this on, et voilà:

Welcome back to right here.

It's fascinating to me that this even requires a technique of some kind. That being where you are seems to be such a challenge for the human mind. That the simple act of coming back to where you already were constitutes a (highly effective) treatment for anxiety and dissociative disorders. And that for the rest of us, luckily free from pathological dissociation, it elicits a profoundly peaceful sense of connectedness.

The human mind is truly odd. So naturally, I get curious. With this funky surfing experience in mind, I started wondering: If not "right here, right now", where the hell are we most of the time? How can I feel like I've just woken up from a dream when the saltwater clears, when my lack of getting pitted is evidence that I was indeed paying full attention the whole time? Well, the answers seem to lie in the question once again: Not right here, not right now.

Not Right Now

Being physically present and being present are two very different things. Ask a student coming out a 4h lecture, or a consultant coming out of their 5th meeting of the day and they'll tell you as much. Our minds evolved as problem-solving machines, and at some point they made a major breakthrough in problem-solving efficiency:

The common animal can only solve the problems it's faced with right now - which means it's all out of problems to solve when the present happens to be calm & peaceful. Not the human animal, though. In a strike of evolutionary genius, we invented "mental time travel" (this is the actual scientific term, I swear), allowing us to solve problems that aren't even here:

- Reliving problems faced in the past: Think replaying last week's argument in the shower

- Imagining problems that could arise in the future: Think "What if I stumble all over my words in tomorrow's presentation?

Our brain's Default Mode Network creates vivid internal counterfactuals (i.e. things that are not) that we get to solve from the comfort of the boardroom or the lecture hall. "Default Mode", because this is literally our default state, arising whenever the present doesn't seem to need our entire problem-solving capabilities.

Neurologically, this is incredibly impressive. Imagining future scenes has the same neurological footprint (i.e. uses the same brain areas) as recalling a memory, which explains why being lost in future scenarios feels just as vivid as being lost in past memories. Indeed, the entire mechanism is surprisingly similar to the pretend play we see in children, making up an internal parallel universe (called paracosm) that feels so real it can take you out of the actual universe for a bit. All without ever leaving your seat.

But as impressive as it is, it comes at a price. Last year, I wrote a whole piece on the Default Mode Network and its role in mental health, so I'll keep today fairly short, but the upshot is best captured in this this 2010 Harvard study titled “A Wandering Mind is an Unhappy Mind”. Using a little iPhone app, researchers randomly pinged participants throughout the day, asking three simple questions:

1 How are you feeling?

2 What are you doing?

3 Are you thinking about something other than what you’re currently doing?

Which makes perfect sense: It doesn't matter what you're actually doing if your mind is currently off in a paracosm where there's problems galore.

But but but but but - all of this assumes that our attention is currently off doing time travel. This wasn't the case in the surfing example. Plenty of problems to solve in the present there, so the Default Mode Network gets a rest. And yet, I get to feel this distance from experience. What's up with that?

Not Right Here

Okay, so we've actually managed to keep our attention on what's right now, for now. Does this guarantee making contact with reality?

Yeah, well. You can probably imagine the answer. As he tends to, Immanuel Kant slides in to spoil the fun. Back in the 18th century, he proposed his school of Transcendental Idealism. Pretty fun name, I must admit. But slightly less fun was its central tenet:

"We can never know things as they are in themselves (noumena), but only as they appear to us (phenomena) through the lens of our mental structures."

Put simply, Kant proposed a disconnect between the reality of things and our perception of them, with a layer of subjective interpretation in between. Taking vision as an example, this implies that we don't have cameras for eyes that project a faithful image onto a mental canvas. Instead, our eyes collect data points like lego bricks and the brain constructs an image out of those bricks, plus a lot of fillers it just happened to have lying around.

A few hundred years and the dawn of cognitive neuropsychology later, and we've got some new words for it, plus a whole lotta evidence. The school of thought is now called Constructivism (slightly less cool), and our understanding of the occipital cortex has made it quite obvious that Kant had a point.

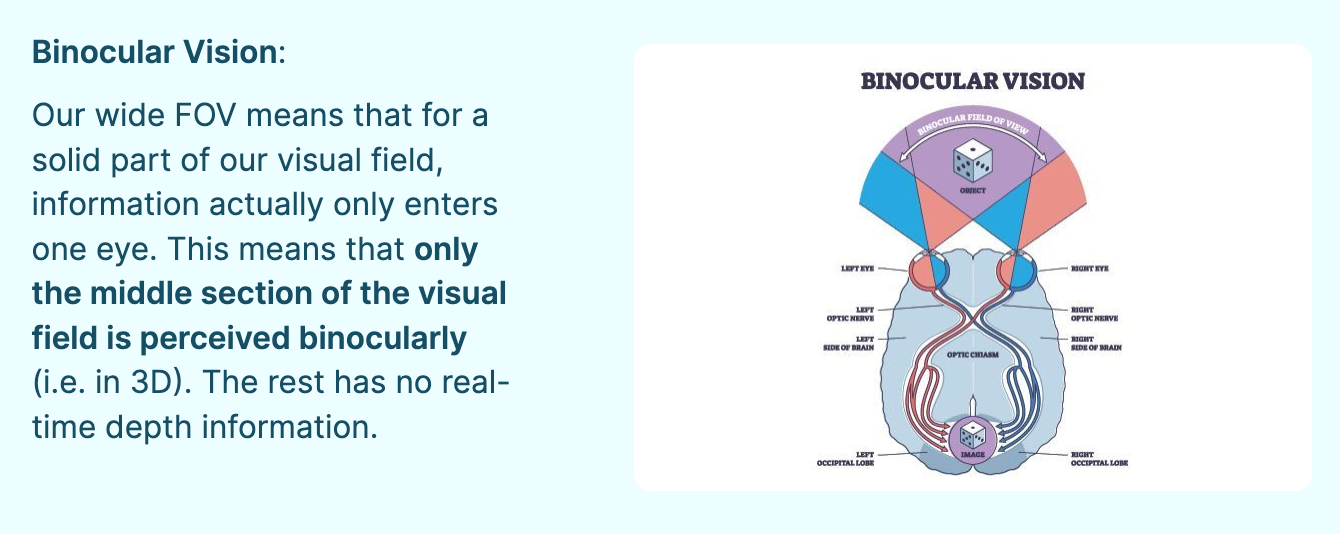

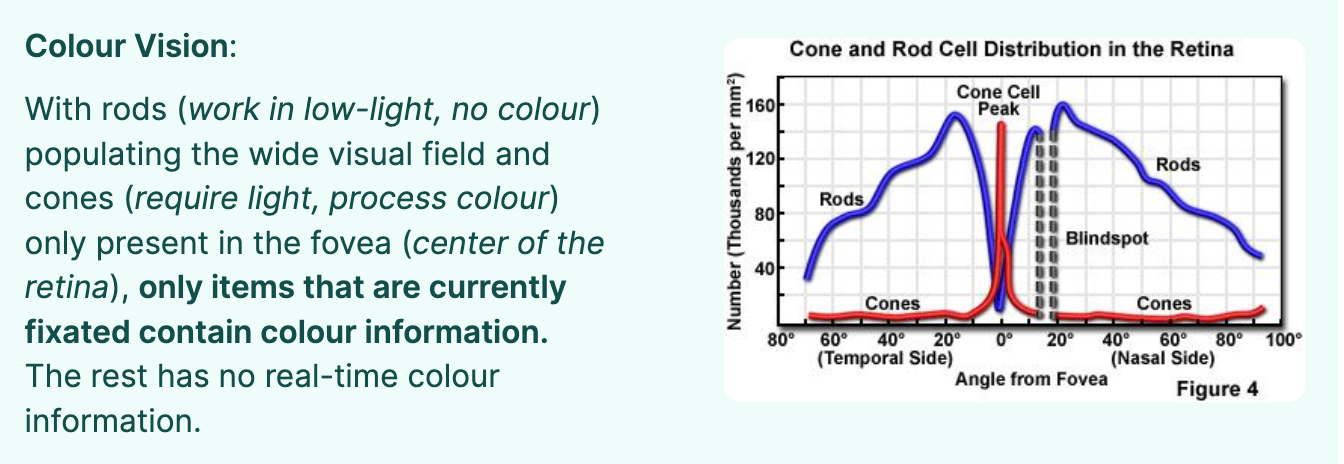

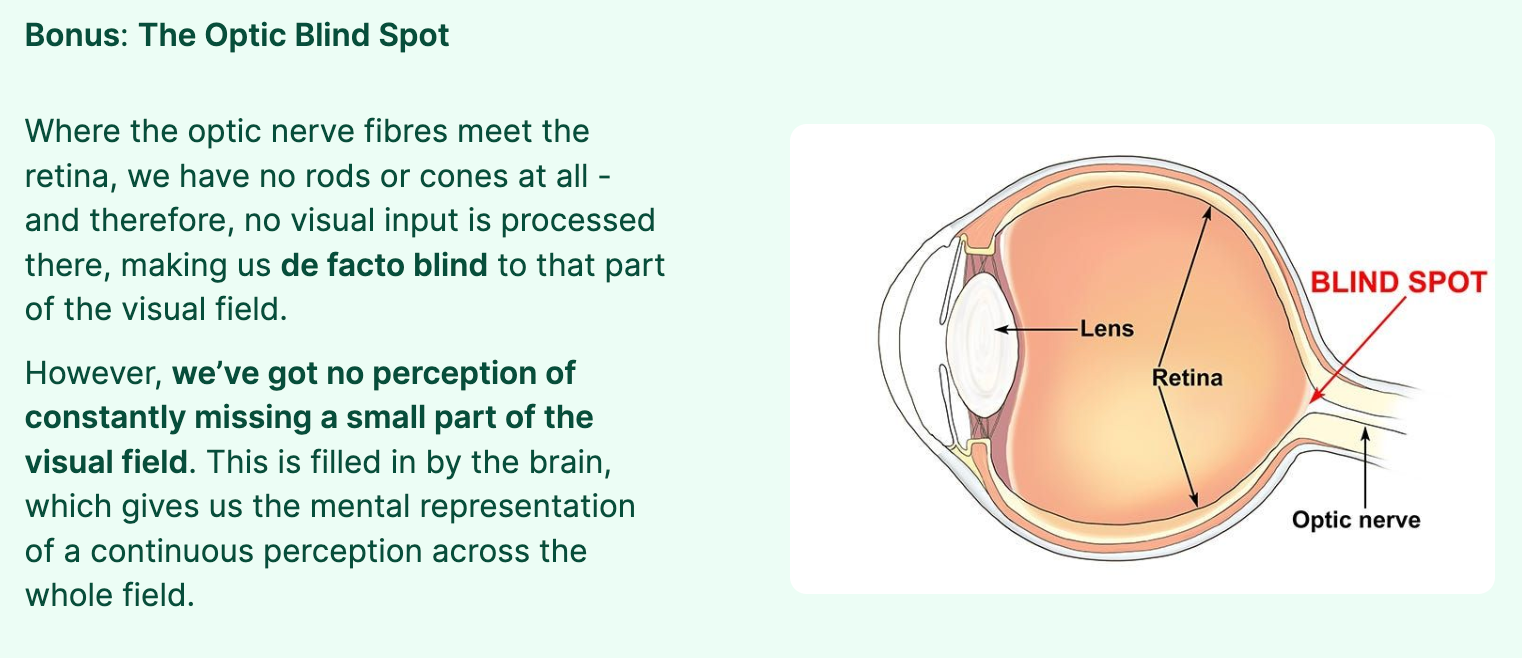

Sticking with vision for a second, we now have clear evidence that our mental perception of seeing the world around us in rich, three-dimensional colour and detail is actually illusory. For most of the visual field, this information is filled in via post-processing:

Of course, this is not exclusive to vision. Our entire experience is constructed in line with our current goals. This isn't too unlike our little paracosms - just that the lego bricks happen to come from sensory nerves instead of the hippocampus (the memory hub). The point here is that for the majority of the time, there hangs this conceptual veil between us and experience.

Even when presumably present and attentive, we're often interacting with concepts instead of the underlying input. I find this most obvious on a plane.

As far as I'm concerned, flying is a ridiculous experience for a human being. Sitting comfortably in an insanely heavy metal contraption, you're soaring above the clouds at unprecedented speeds with views that were never before possible for humans. A child in a window seat will act accordingly, with a bit of "wow" and a bit of fear and a lot of overall excitement. A perfectly adequate response to the sensory input. But the businessman in seat 3A disappears into a newspaper as if seat 3A were in his living room and not 10,000 meters above the ground.

Surely this is worth some awe.

Both the child and the businessman are experiencing the same stimuli, yet their subjective reality is fundamentally different. Why? Well, the businessman is simply on a flight. The metal contraption, the insane speeds, the unprecedented perspective, the occasional turbulence and everything around it - they've all been combined into a single concept: "a flight". He walks into a plane, seat 3A cues the mental schema "flight" and the madness that follows is deeply familiar to him. Simple habituation.

Recalling that experience is always constructed in line with our current goals, this makes perfect sense: Evoking the concept ensures sober functioning in situations that have proven to be devoid of problems. While the kid remains supremely excited, over in seat 3A someone is currently catching up on some sleep, or checking some emails, or doing whatever else is goal-relevant. None of this were possible if the nervous system were currently processing raw reality (insane speed and height etc).

But there's a price paid here, and it's that sense of distance. Placing this heavy conceptual layer between yourself and the world, you're no longer in contact with the world in the way the child is. Interacting with concepts can be highly effective in goal pursuit (e.g. the pursuit of a nap), and I'm not arguing against it at all. Not just because it'd be absolutely futile to argue against human nature. More because that price is often justified.

Concepts and counterfactuals are part of what make us so brilliant in the first place, allowing us to navigate the madness around us much more effectively. They just also happen to drive us mad half of the time. "A wandering mind is an unhappy mind", and that's considered in the evolutionary equation: Our brains didn't evolve to be contentment machines, but survival machines. And if a little lost joy is the price to pay for a little more problem solving practice, that's resources well spent for the human animal.

It's tough out there for the human animal, eh? Well. If you've got time to read (or write) stuff like this, you're currently living in a situation that, for most of human evolution, would've been considered heaven on earth. Ubiquitous access to fresh water, food grows in the supermarket, and I don't seem to recall having to defend myself against any wild animals recently. But the very mechanisms that got us here in the first place aren't optimised for enjoying the fruits of our labour.

Not optimised, but it's not impossible either. We just happen to be smart enough to outsmart ourselves. The brain tries to figure out the brain (literally Neuroscience), and sometimes it happens to land on something that works. Like grounding. A way to bypass the habitual disconnection from raw experience, lifting the veil of concepts just enough to touch reality again. Bottom of your feet, and all that.

Tapping into that which really is, prior to all the problem post-processing that our conceptual minds like to add, we usually find that things are actually pretty damn alright. Making contact with raw experience (for example through sensory reorientation) exposes us to the funky fact that we're actually here. That the lights are on. That it's like something to be you, and that something happens to be incredibly vivid.

Sidestepping concepts for a second can invite an incredible state of wonder into our lives again. The opening example was one of those - the feeling of re-emerging into the insane scenery of Unstad Beach felt more surreal every time the salt cleared my eyes again. There was an unparalleled sense of gratitude that simply gets lost in the concept: "Surfing Lofoten" is just a bunch of words, like "flight" or "sunset" - but the underlying raw experience is something entirely different.

Not that this needs anything extraordinary. Grounding, seen as the practice of returning to where you already are through your sensory input, simply requires that you are somewhere. And I think most of us are somewhere most of the time. Practiced enough, it becomes a simple voluntary shift, just like you can switch between looking through a window and looking at a window. Sitting here typing this at a regular old table in regular old Berlin, it might be the feeling of my fingers hitting the keyboard or seeing the ridiculous number of lemon-themed decoration (sitting in the lemon.markets office right now), and the same feeling of presence arises. I'm here, the lights are on, and I believe that is a rather miraculous circumstance.

Of course, I'll return into the world of concepts again in a minute, and surely stay there for a while. Being lost in thought (i.e. interacting only with concepts) just so happens to be the default state of our mind. But it need not be our only state. Every once in a while, we get to take a break if we want. The opposite of dissociation lies under the bottom of your feet.

Studies Linked:

Heart Rate & Cold Water: Resting Heart Rate Affects Heart Response to Cold-Water Face Immersion Associated with Apnea, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10295257/

Attention & Awareness are two separate things: "Growing evidence for separate neural mechanisms for attention and consciousness" https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13414-020-02146-4

Grounding as a Therapeutic Tool: "Dissociation", https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-61416-4_5

Mental Time Travel & What sets our Mind apart from other Animals? "Understanding Human Cognitive Uniqueness", https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-062220-051256

Memories and Imagination have the same neurological footprint: "Using imagination to understand the neural basis of episodic memory", https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18160644/

Being present determines Well-Being: "A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind", https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1192439

Kant, Phenomena & Noumena: "Kant’s Transcendental Idealism", https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-transcendental-idealism/#PhenNoum

Comments ()