How do you trust your Intuition?

“How do you trust your intuition?”

When a friend asked me this question today, I realised I don’t really have a solid answer. Looking back on a rocky relationship with my intuition, I decided it's worth an exploration. So here it goes: The Scientific Case for Trusting your Intuition.

Throughout my first year of studying psychology, I developed this idea that I was now the rational guy. If there’s no study on it, I don’t believe it. If there’s no well-structured argument for it, there’s no point here. As a result, the idea of intuition became, in my mind, lazy and incomplete. Intuition was just the form of argument for those who can’t be bothered to actually think.

At this rate, I strolled through life on my imaginary high horse of rationality, convinced that this is the right way to think and everything else is esoteric & pointless. But as I learned more & more about psychology, this horse started stumbling. The first defining stumble came courtesy of a groundbreaking 2005 study thrillingly named:

😴 Failure to Detect Mismatches Between Intention and Outcome in a Simple Decision Task

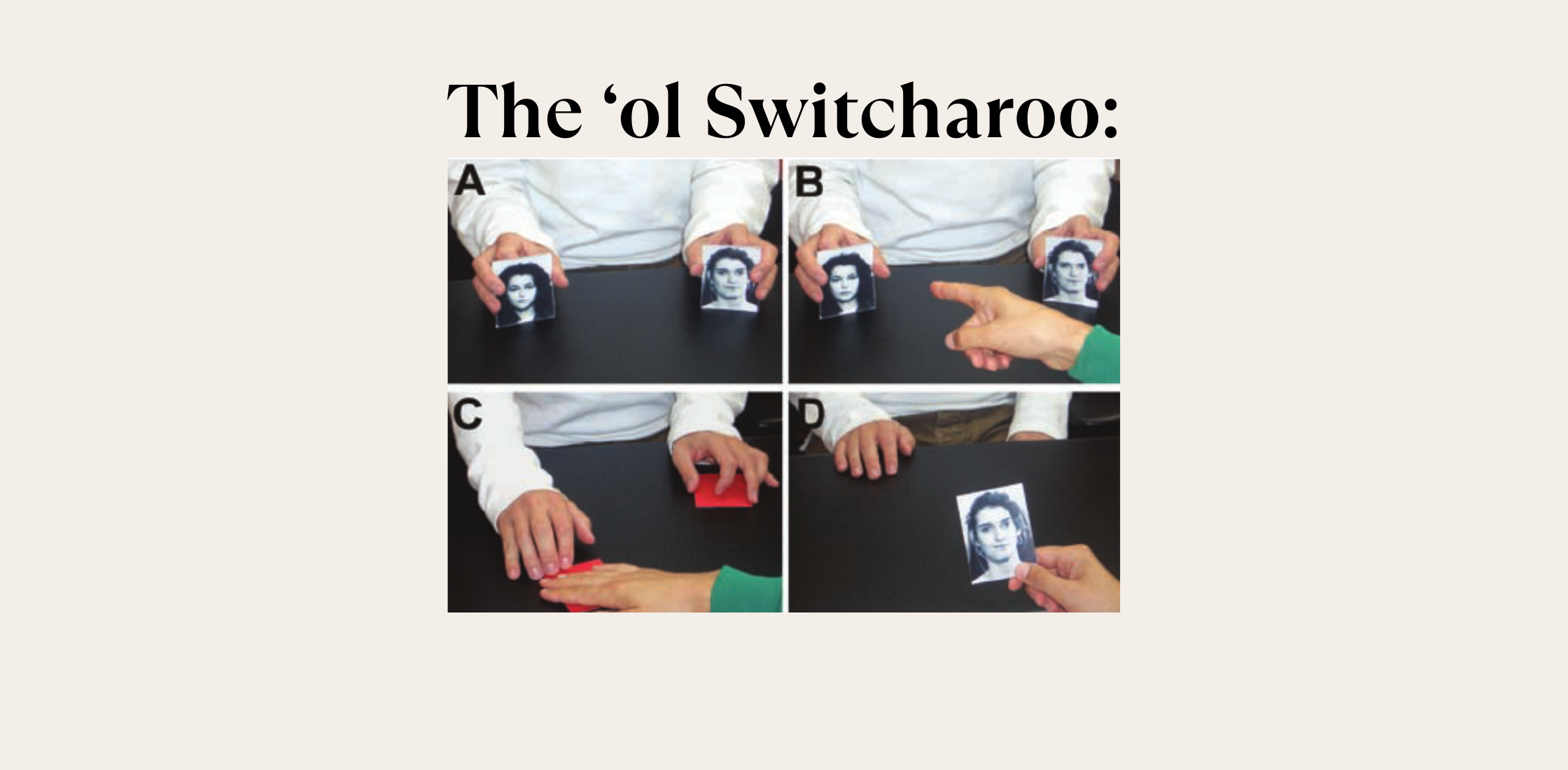

Trust me, behind that boring name hides a fascinating insight about our presumed rationality. In the study, researchers gave their participants a very simple task:

Look at two faces and decide which one they find more attractive.

Afterwards, they were asked to explain their choice - Why did you choose this person? Naturally, they proceeded to give a perfectly rational explanation of their thought process: “I really like earrings and their smile was lovely”. Simple enough, right?

The catch: With a little sleight-of-hand magic trick, the researchers mixed up some of the cards. This way, they showed the participants the person they had not chosen, asking them to explain why they had chosen them.

What do you think - How many people happily explained their “choice” instead of detecting the mismatch? Really - have a moment to think: If you had eggs on toast for breakfast and I asked you why you decided to eat porridge this morning, would you give me a great case for the health benefits of oats?

Well, if you’re like 73% (!!) of participants, you would. They sat there giving their perfectly rational reasoning for a choice they never made. Telling lovely stories about what they thought while they chose that person - but they never did.

It’s a bit of a head-twister, right? My whole life I was convinced that when someone asked me why I do what I do, the answer my mind gives me is an accurate picture of what happened. Like the instant replay in sports, a direct representation of what lead to the present moment.

In contrast, the study proved that what’s going on is actually guesswork. It’s not necessarily wrong. But it’s also not necessarily right. There’s no accurate record - no replay - of what happened in the infinitely complex system of neurons that decided to choose Jane over Julia. So when you ask for a replay, that very same system will just give you its best guess of what happened (even when it didn’t) and dress it up as a replay. It’s not a record of the past brain, it’s the present brain playing detective and coming up with a plausible story.

When I learned about this little costume party going on in my oh-so-rational brain, the facade of the high horse took a little hit as well. I thought I had a Live-TV access to the office of my rational mind, but in reality I was just watching The Office (UK or US, your choice). It’s great to have, but probably shouldn’t be the sole fundament of your world.

💡 In Defense of Rationality

Now, I feel it’s important to clarify: My point is not that rational thought is a complete joke & one should never make use of it. The point here is that when you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Granted, there’s a bunch of nails in the world. Problems that have a right answer - they are perfectly approachable by rational thought.

Take statistics, for example: If you roll dice, the chance of rolling a 6 is 16.7% (or 1/6). It’s not more, it’s not less. How I feel about it doesn’t matter in the slightest.

Or take the logical argument of causality: If a) a car will not run without gas and b) I don't have any gas in my car, then c) my car will not run. Perfectly factual, thank you brain.

But here’s where the issue arises: The brain will apply rational thought whenever you tell it to - no matter if it’s actually helpful and/or possible in that context. Without any disclaimers that it’s just guessing, it’ll give you the definitive answer for a question without a definitive answer. You’ll never definitely know why you chose toast for breakfast - because that level of depth is simply not accessible by conscious thought. Still, all you need to do is ask and the brain will give you a perfectly plausible narrative of all the causes & conditions that lead to your brekkie choice.

So here we are, 900 words into a piece on Intuition and I keep rambling on about Rationality. What’s up with that? Well, let’s come back to the opening question: “How do you trust your intuition?”.

🛠️ Opening the Toolbox

To me, beginning to trust my intuition only began when I recognised the nature of rational thought. Here was this thing I had blindly trusted as the ultimate truth for ages, turning out to be nothing but an approximation - a best guess of what’s going on in the black box that is neurological processing. A great guess, don’t get me wrong. But once I found that it was merely a tool - great for nails, mediocre to flip a pancake - I couldn’t help but wonder what other tools I’d been sleeping on.

The subsequent closer look into the scientific conceptions of intuition revealed that I’d been fooled by a false dichotomy. In other words, I’d assumed rational thought and intuition to be two different things when in reality, they exist inseparably on a continuum (→ Cognitive Continuum Theory). In a mind incapable of pure rationality, then, the question isn’t if intuition should be involved - it’s how much. In other words, what degree of the process should be available to conscious deliberation.

Take a classic case of "rationality": The math problem. If I ask you to answer 481+728, conscious calculation is the way to go. But once you start calculating, you deconstruct the task - and I'll bet you won’t start counting with your fingers to figure out 8+1. That answer will just come to mind naturally. This is called inferential intuition - the habituation of previously analytical processes. Basically, this used to be a conscious task (back when you were in primary school), but you’ve performed it so often, it’s become subconscious. You can’t tell me how you know - you just know. There you go, trusting your intuition already.

But intuition isn’t limited to low-complexity tasks - it also comes in on the other extreme. Decisions so complex it’s practically impossible to find the right answer. My most vivid example was the decision to move back to Australia this year. Should I stay or should I go? For a week straight, I was trying to find the right answer. Pro/Con-lists and all, I tried to rational-thought my way through to certainty. But unlike 8+1, I have no access to the right answer here - the complexity of the human life is simply beyond the reach of lists & arguments. So it took my good friend Julius taking me aside and telling me “Man, who are you tryna fool - you know the answer already.” to realise I’d been hard at work flipping pancakes with a hammer.

I knew the answer based on holistic intuition (in fancy words: “judgments based on a qualitatively non-analytical process […] by integrating multiple, diverse cues”). Trusting that intuition wasn’t a guarantee that I’d found the right thing - mainly because there’s no “right thing” to find here. Instead, it was acknowledging my limitations and going with my best possible tool.

You see, conscious thought is limited by a) the confines of language and b) the specifics of that day. If I, for example a) don’t know the word for something and/or b) it doesn’t come to mind while I’m brainstorming, it won’t end up on my Pro/Con-list. Holistic intuition, on the other hand, takes in the entirety of the mental landscape to somehow deliver a feel-able answer.

This somehow process is profoundly unhelpful in contexts where we can arrive at a rationally right answer. If I wonder, for example, if excessive sugar consumption causes health problems, I can happily ask my holistic intuition. Maybe it’ll tell me “No, sugar is lovely.” and be on its way. Or I can conduct a study, run the numbers and find the right answer. Trusting your intuition here is like using the kitchen spatula to hammer in a nail. The artform, then, is to distinguish pancakes and nails.

❓ How do you trust your intuition?

The answer to the opening question, then, is a process. Learning to trust your intuition, to me, means learning when to look for the right answer and when to acknowledge that the best guess is all you get. It's letting go of the delusion that what you feel constitutes the definitive, right answer (mainly because there's no such thing - or at least not accessible to us). Trusting your intuition means acknowledging intuition for what it is - nothing more, nothing less. It’s the best available tool for the job, so you might as well use it.

Comments ()