Your Brain on Doing

This is Part 2 of the 3-Part Balance Series. For this to make sense, I’d recommend reading Part 1 first 🤝.

“Hard choices, easy life. Easy choices, hard life.”

If you make hard choices now, future you will be grateful. If you take the easy road today, future you will struggle.

This quote, attributed to Polish Alcoholic-turned-World-Champion Jerzy Gregorek, is passed around in motivational circles like a holy grail. And while I appreciate its message today, misunderstanding this sorta stuff is what leaves you burnt out at 22.

Now, Gregorek isn’t to blame here - this one’s on me. When I first learned about this idea, I just made it fit into my existing mental model. Making “hard choices”, to me, meant pushing back any sort of rest, and instead Doing more. I can still vividly remember telling a friend that I don’t make a difference between weekdays and weekends - thinking that that’s a good thing. Sitting idle (→ Being), even for 10 minutes, seemed to me like the easy choice - so I avoided it at all cost.

But as we learned last week, I was fooling myself. Yeah, I was avoiding it - but not because it was the easy choice.

If you recall from last week, the neural circuits that come alive when we’re not focusing on a task (Default Mode Network) create a highly unsettled state. The Monkey Mind is so full of rumination and uncomfortable questions, people literally choose painful electric shocks over sitting with themselves. Still, this is also the exact state my therapist taught me to sit with when working with the Burnout - because those were the exact questions I had to face to move forward (more on that next week 🙃).

So as it turns out, Being is actually the hard choice. Not blindly distracting myself with more Doing. But this seems so counterintuitive. Doing is easy, Being is hard. Huh? This isn’t what productivity gurus told me for years. Well, it’ll make more sense once we compare the brain states.

Remember - the Monkey Mind only comes on when there’s no task to focus on. So if you want to quiet the monkeys, the easiest way is to focus on a task. So far, so easy. But what happens once you do?

Your Brain on Doing

We all have an idea of how things should be. An ideal state of the world built on expectations, desires and instincts:

- The level of water in your system.

- The level of status in your peer group.

- The way the room should look.

- The way you should look.

At any moment, your brain is monitoring the world inside and around you & comparing it to an ideal. If there’s a mismatch between the two, you generate a new goal:

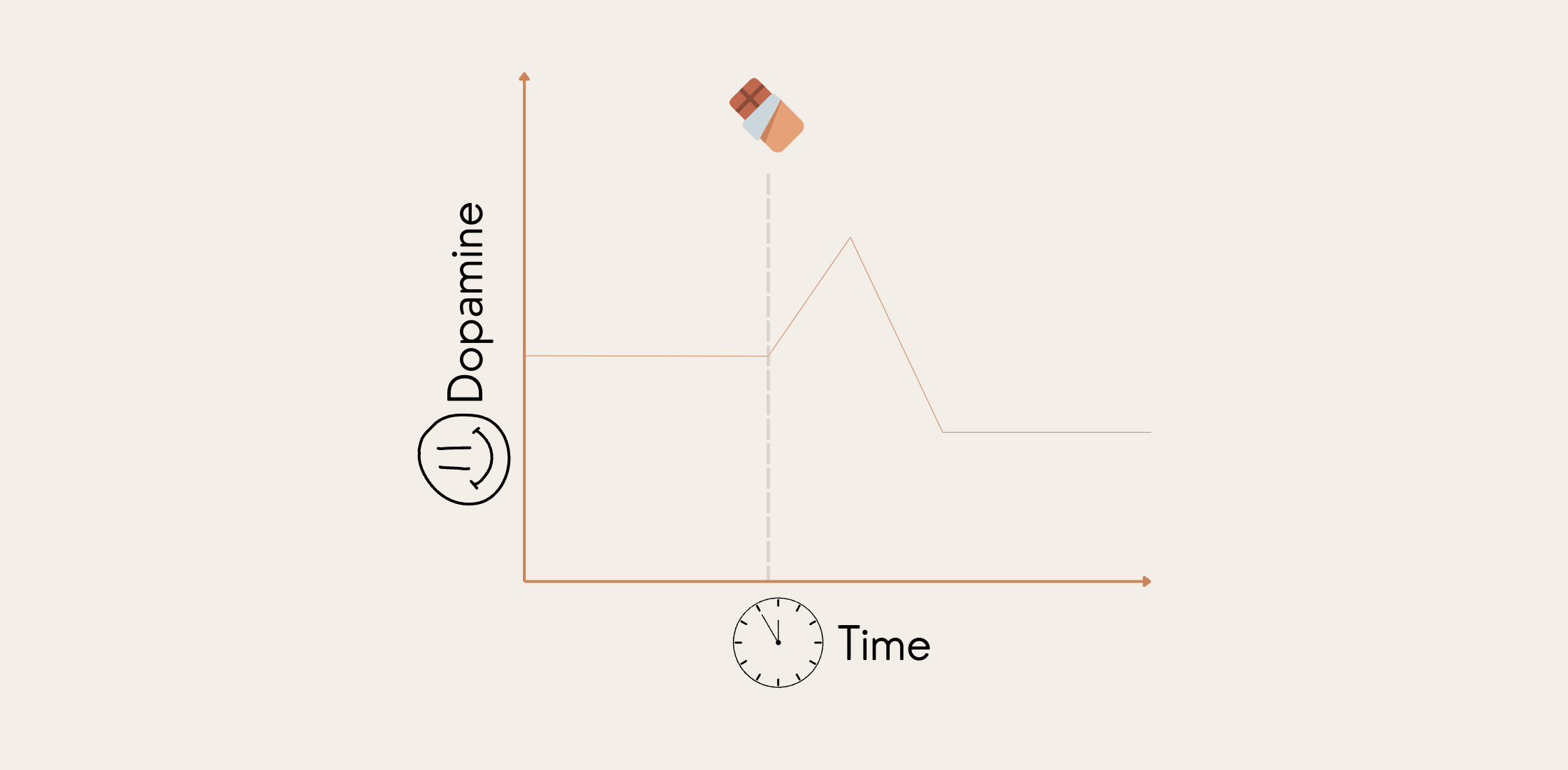

What used to be “Find Berries for Survival” has become “Publish a Blog” or “Get a six-pack”, but the mechanism has remained the same since humans roamed the Savannahs. We have this so-called “discrepancy monitor” that sets goals and promises Dopamine (a feel-good neurotransmitter) for their completion. If you make progress, you get a little hit of the feel-good stuff. If you reach the ideal state, there’s a big hit. This is the system that defines the Doing mode.

For goals, it’s smart evolutionary design: Pursuing a goal feels rewarding - but that feeling quickly vanishes to make space for the next one. But it’s also what makes Doing so effective at capturing your time: Every step is another piece of chocolate, and there’s always a next goal to pursue.

Not that it stops at neurobiology. To add to the internal reward system, there’s a lot of external validation in Doing. German culture is especially big on this, but we’re not the only ones socialising our kids with this simple premise: Doing is inherently better than Being. One of our most common sayings literally translates to “First the work, then the enjoyment."

Call it work ethic. Call it discipline. Call it whatever you want, but the message that’s sent to kids early on is simple:

The more you do, the better. The earlier you do, the more impressive it is.

So you do. Day in and day out, resolve all of the discrepancies your brain can come up with. Which isn’t all bad, of course. This restlessness is why humans didn’t stop after inventing the wheel, rather striving for the rocket. The same restlessness that drives us to achieve our dreams. And don’t get me wrong - I’m not arguing for everybody to stay in bed forever. I’m just arguing for Balance.

If you put it all together - an uncomfortable brain state (Being) with a perfectly fitted off-switch (Doing) that is pleasant, cyclical and praised by others - it’s truly no surprise it’s so easy to get lost in running. So easy that we completely lose sight of the balance - even on breaks:

I spent the last 5 months surrounded by backpackers from all around the world. These aren’t the first people you’d think of when imagining a Doing-focused crowd. But if you listen closely, there’s always a common phrase. “Well, first I did Laos and Cambodia.”, they’ll tell when asked about their trip. “And tomorrow, I’m doing the Tegenungan Waterfall.” This phrasing is so ubiquitous, I started adapting it myself. And when I caught myself, I felt like an absolute idiot.

Suddenly, even a country is something you do. The trip is another thing to check off, the places you’ve seen are another achievement. So when it’s not work and ambition, it’s travel - but you’re always defined by what you do.

To me, this is the core of the problem - and the reason I’m grateful for the Burnout. If you never stop running, you never have to see what you’re running from. You never have to ask yourself who you are without all the Doing. But when you’re forced to stop, the question becomes inescapable.

Apparently, I had equated my worth as a human being with my ability to Do for the last 22 years - and I had never noticed because I got so good at it. I never felt problems with my self-worth - because I always did enough. I never felt a hole, because I always filled it. But that doesn’t mean that there wasn’t a hole.

This is where the whole argument leads. I tell this story to illustrate the incredible blind spot we seem to develop through this constant movement. I don’t know what you’re running from - or rather if. Maybe you’re fine, maybe I’m just weird. Entirely possible, but the prevalence of mid-life crises makes me think I’m not entirely alone.

So next week, we’ll try to illuminate this blind spot a little. I was taught some wonderful little questions that helped shed light on this whole conundrum. Now, recognising the hole doesn’t make it disappear - but it opens the door to start healing it. So if you’re up for it, join me next week for the practical part.

If you don’t wanna miss the next part, Subscribe to get it delivered straight to your Inbox 😏

Comments ()